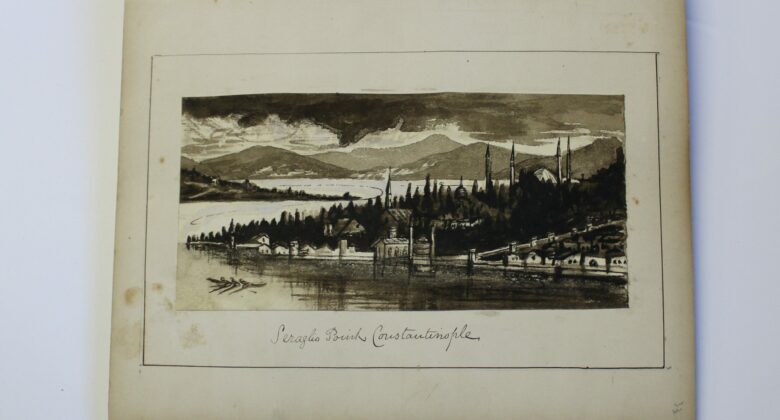

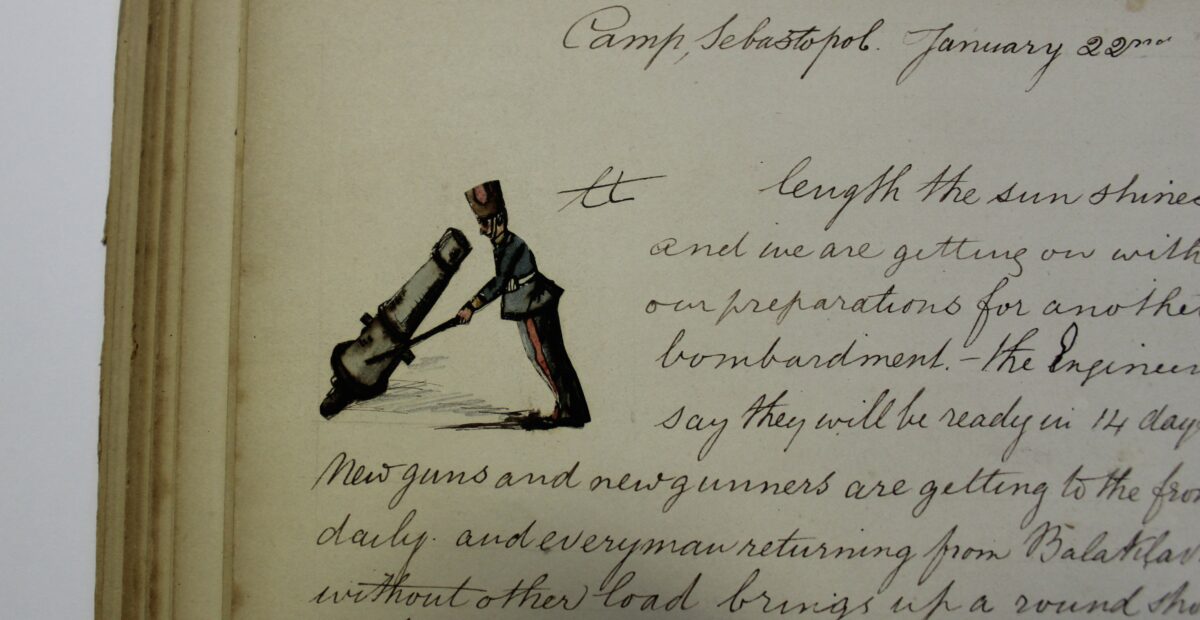

Extracts from an officer’s diary from the 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot have been preserved since 1855 which document the gruelling conditions at the frontline of the Crimean War. The book contains diary entries and sketches, and, at the back, a list of soldiers who died during the war, including their names, rank, date, and cause of death. This is a particularly important record as it shows to the extent to which soldiers died of illnesses such as cholera and dysentery as a result of the lack of provisions.

It was acquired from A W H Parr Esquire and presented to Brigadier S N Acland before being gifted to the museum in 1976. The diary was initially believed to have been written by Lieutenant Charles Robert Shervinton. However, with research conducted by Colin Robins ahead of the publication of the diary in 1994, it is now attributed to Lieutenant Richard Lluellyn.

After a few long weeks on board the ship the Prince, the 46th regiment of foot arrived to the camp on 7th November 1854 near Balaklava. The following extracts are taken from the diary:

‘Just outside of Balaklava we met a string of mules bearing wounded Russian prisoners-a ghastly crew, some of them hanging forwards over their strappings quite dead…On our arrival we found no one expecting us or knowing anything about us or our affairs. Neither tents or rations had been provided for us. So, without food or shelter we passed our first night in the Crimea, lying round our arms in the open air under a heavy rain…Every General and staff officer in our division was killed or wounded. The people who are left appear dazed and stupefied and unable to give us an idea of our position or our chances…

This account of ‘dazed and stupefied’ soldiers seems to describe what is now understood as a Combat Stress Reaction (CSR). CSR is a natural psychological response after enduring a traumatic situation in combat.

‘Down the valley, the ground is covered by helmets, knapsacks, bent bayonets, empty pouches, which are fast being appropriated by the sailors from the transports at Balaklava as “trifles from Sebastopol,” to take home to their sweethearts. Where men have struggled long or died in agony, the grass and bushes are torn up and clotted with blood not washed away. Our burial parties are still busy finding bodies hidden in the bushes or water courses.’

26th November 1854

‘Twenty-eight men of our regiment have died of cholera during the last forty-eight hours. The strongest men – those who have never been ill before – die soonest, never seeming to make a struggle. It is an awful disease to witness. Last night I was talking to Elijah Pryme-pioneer of my company- the cheeriest, strongest fellow in camp; he was as full of life and as ready to help anyone as usual. The morning what cholera had left of him was carried past me – the face so distorted that I could not recognise a feature.’

6th December 1854

‘Today we count 160 dead out of the 600 men of our regiment who landed a month since: our splendid band is quite silenced; the big drummer has been killed by a round shot, the 1st clarionet is dead of cholera; and the poor child who played the cymbals has lost a leg…My light company tents are next the hospital marquee. I hear the groans of the poor wretches dying there all through the night, and the first sight which greets me when I open my tent door in the morning is a row of the night’s dead; this morning I counted eleven bodies. Being on inlying picquet, and no parson to the fore today, I had to bury them’

28th December 1854 On board the barque Rockliffe in Balaklava Harbour:

‘A severe attack of fever having made me useless in camp, our Brigadier got me, unasked, a fortnight’s leave to go on board ship. There is no sort of conveyance for sick officers, and Vesey failed in an attempt to borrow an ambulance cart from the French, so I was tied on my pony….I was hoisted on board in the same manner that horses are embarked and placed in a wooden partition which contained neither mattress nor blankets….At night I counted the ship’s bells-and fell a helpless prey to the huge cockroaches with which this ship- an old sugar trader-swarms…a doctor looked into the saloon, but, calling out ‘I see you’re all right here!’ was gone without my being able to attract his notice.’

‘Forde and Algy Garrett got down from camp to see me, bringing the following dreary items of news: Our regiment is now reduced to 60 duty men: many have been frozen to death and crippled by frostbite: no ration of fuel is issued yet, and the only resource for cooking or warmth is to grub up roots, an almost hopeless task now that the ground is covered by snow.’

January 1855

The Lieutenant returns to camp mid-January and shortly after stops recording his daily life in such detail as ‘the foregoing extracts…suffice to show that the ills which overtook our regiment were in no way of our own making.’ On the 9th March 1855, the regiment were ordered home on board the Holyrood. ‘[I] Went for a farewell walk down the valley of Inkerman. All the country round has become…covered by crocuses, lillies, Hyacinths and the little Star of Bethlehem…Far down the valley we found the bodies of two of our men of the A Company, lying under thick acacia bushes. Vultures or wild dogs had got inside their greatcoats and eaten all their flesh away, so that the skeletons rattles inside. I cut off some of their buttons as souvenir de la guerre.’