Forward Psychiatry

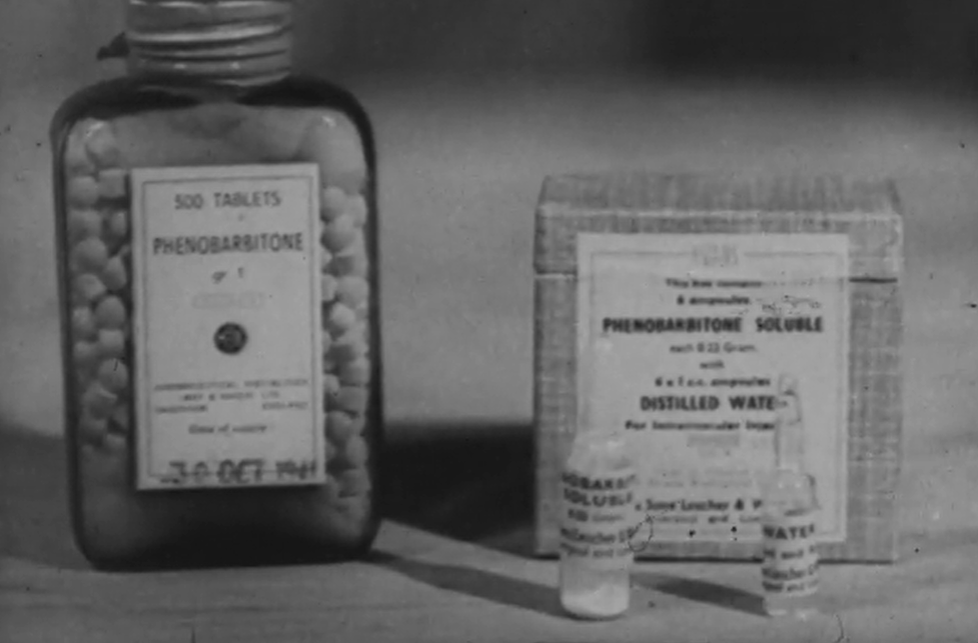

Military medics employed the principles of ‘forward psychiatry’. They treated psychiatric casualties as soon as possible. Patients remained close to the front line and medics made it clear they expected a full recovery. Treatment was limited to sedation, sleep, food, insulin for weight gain, occupational therapy, and physical training. Patients wore their uniform throughout their treatment to keep focus on their military role. The aim was to quickly return the soldier to combat, offering only short-term relief.

Stills from ‘Field Psychiatry for the Medical Officer’ (1944)

Credit: Wellcome Library. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Exhaustion centres were set up in Normandy in preparation for the 1944 D-Day landings, one for every corps. If patients who were admitted to these exhaustion centres did not recover within 48 hours, they would be transferred to the 32 General (Psychiatric) Hospital for more advanced care. As the campaign progressed, the exhaustion centres and hospital quickly became overwhelmed. By mid-July 15% of battle casualties were exhaustion cases.

Stills from ‘Field Psychiatry for the Medical Officer’ (1944)

Credit: Wellcome Library. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Stills from ‘Field Psychiatry for the Medical Officer’ (1944)

Credit: Wellcome Library. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

‘’Field Psychiatry for the Medical Officer’ was produced in 1944 by the Directorate of Army Kinematography. This was a War Office service which produced educational and entertaining films for the British Army. The film follows the experience of Private Wragge, who develops battle exhaustion after six days of exposure to mortar fire. He is ‘cured’ after a short stay with the field medic and returns promptly to his unit on the front line. In reality, return to duty rates were low and many patients were discharged from the army.

Credit: Wellcome Library. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Credit: Wellcome Library. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

The film encouraged commanders and medical officers to take forward psychiatry seriously. Doing so would help to alleviate the hospitals and keep as many men on the front line as possible during the crucial 1944 Normandy campaign.

Many commanders believed that soldiers were faking their symptoms, or that battle exhaustion was down to lack of courage. Some believed psychiatrists undermined the battle spirit of their troops by offering an escape route. Even Winston Churchill wrote in 1942:

“I am sure it would be sensible to restrict as much as possible the work of these gentlemen … it is very wrong to disturb large numbers of healthy normal men and women by asking the kind of odd questions in which the psychiatrists specialize.”