Mental Trauma and the Crimean War

“It is difficult to recognise in their haggard faces and ragged clothing the gay soldiers who left us the other day. Every general and staff officer in our division was killed or wounded. The people who are left appear dazed and stupefied and unable to give us any idea of our position or chances”

Lieutenant Lleuellyn

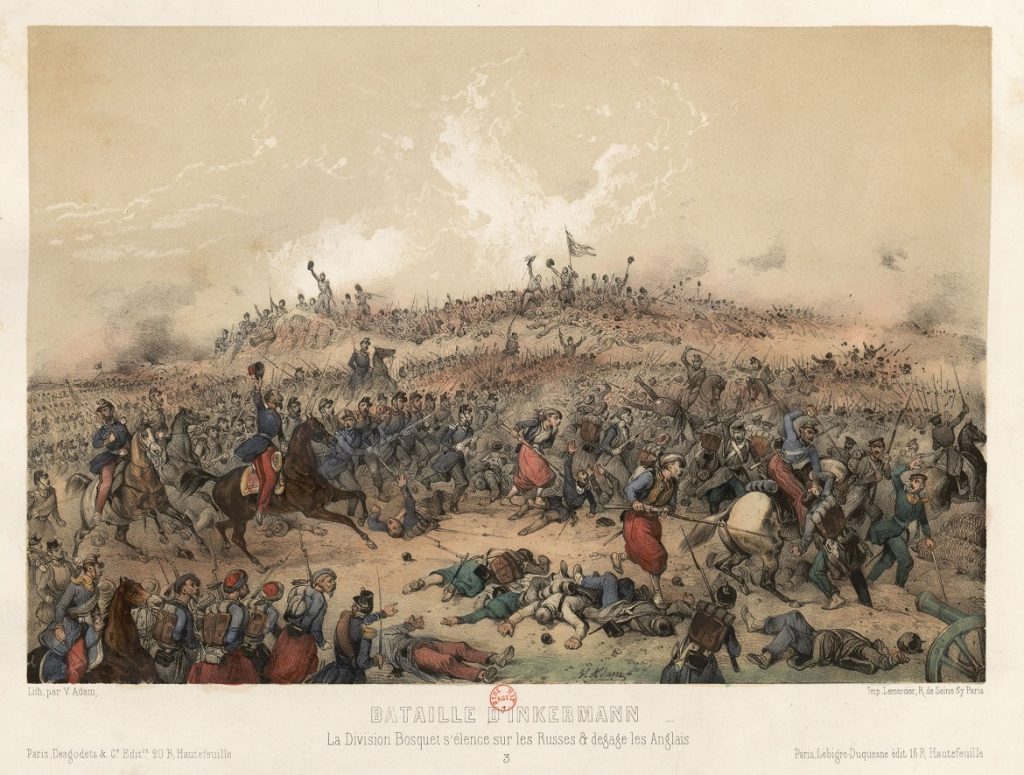

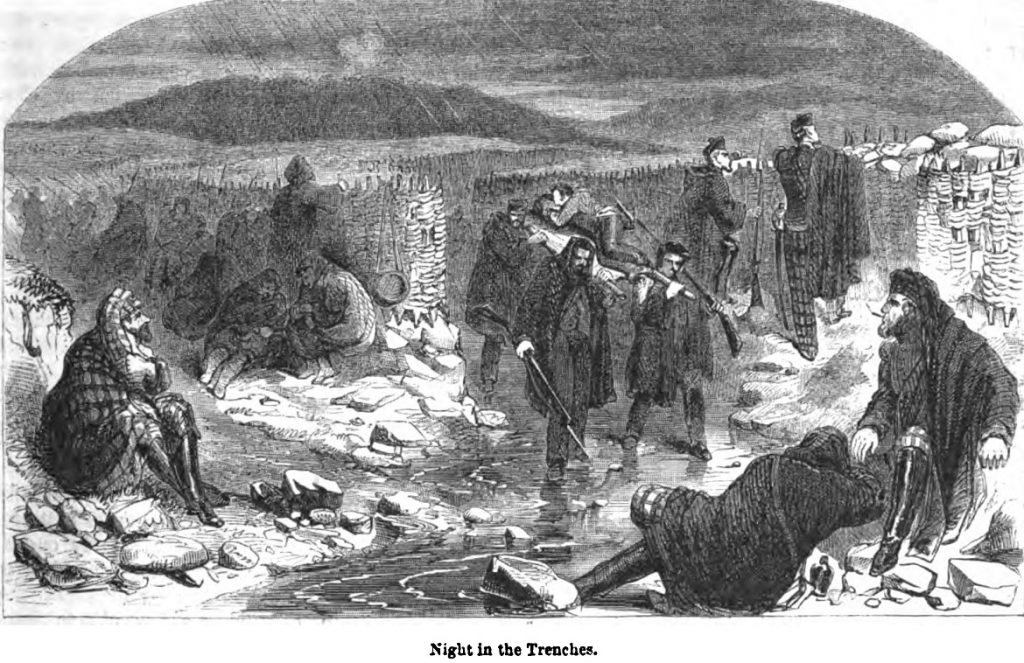

This is an extract from the war diary of Lieutenant Lleuellyn of the 46th Regiment of Foot. Lt. Lleuellyn visited the Crimea two days after the Battle of Inkerman on the 5th November 1854. Troops there not only endured the horrors of a brutal battle but were hit by a terrible winter. They ran low on rations, winter clothes, medical supplies, tents, and fuel. They were ravaged by disease and starvation. Lt. Lleuellyn’s account of ‘dazed and stupefied’ soldiers seems to describe what is now understood as a Combat Stress Reaction (CSR). CSR is a natural psychological response after enduring a traumatic situation in combat.

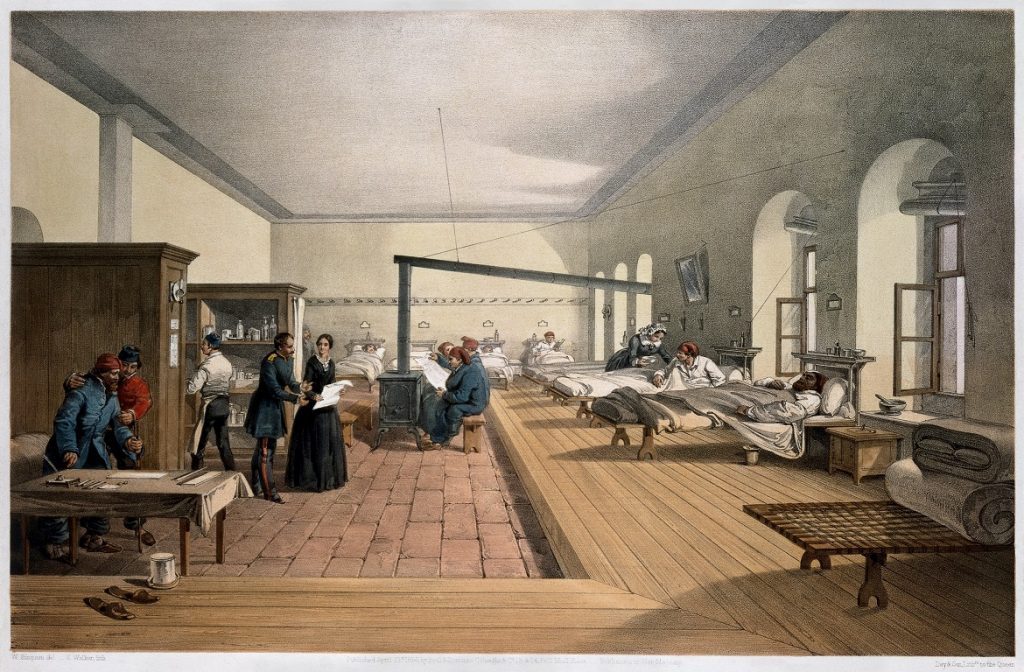

Florence Nightingale was appalled by the conditions that the soldiers endured in the Crimea. She was intent on ensuring her patients had adequate light, better food, and fresh air. Nightingale understood that a more holistic approach to nursing benefited mental wellbeing. A sound mind would then improve people’s physical health. In her book, ‘Notes on Nursing’, Nightingale highlighted the importance of mental wellbeing during a patient’s recovery:

“Volumes are now written and spoken upon the effect of the mind upon the body. Much of it is true. But I wish a little more was thought of the effect of the body on the mind. […] how the very walls of [the patient’s] sick rooms seem hung with their cares; how the ghosts of their troubles haunt their beds” (Chapter 5)

Credit: Wellcome Images. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

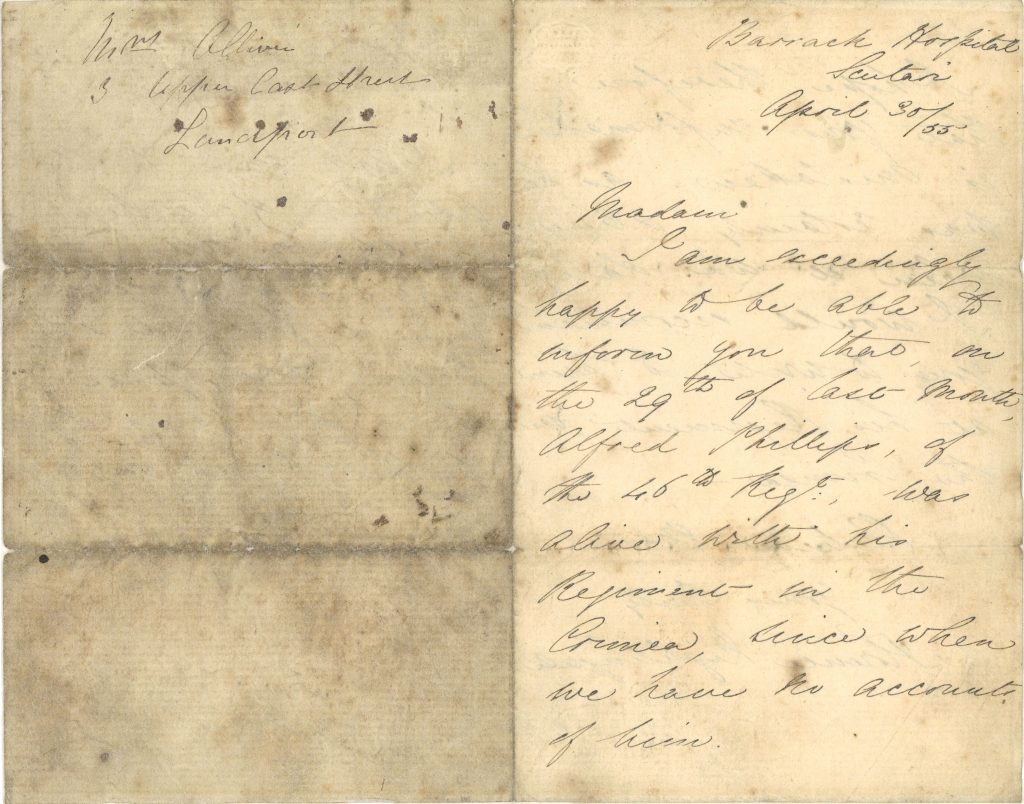

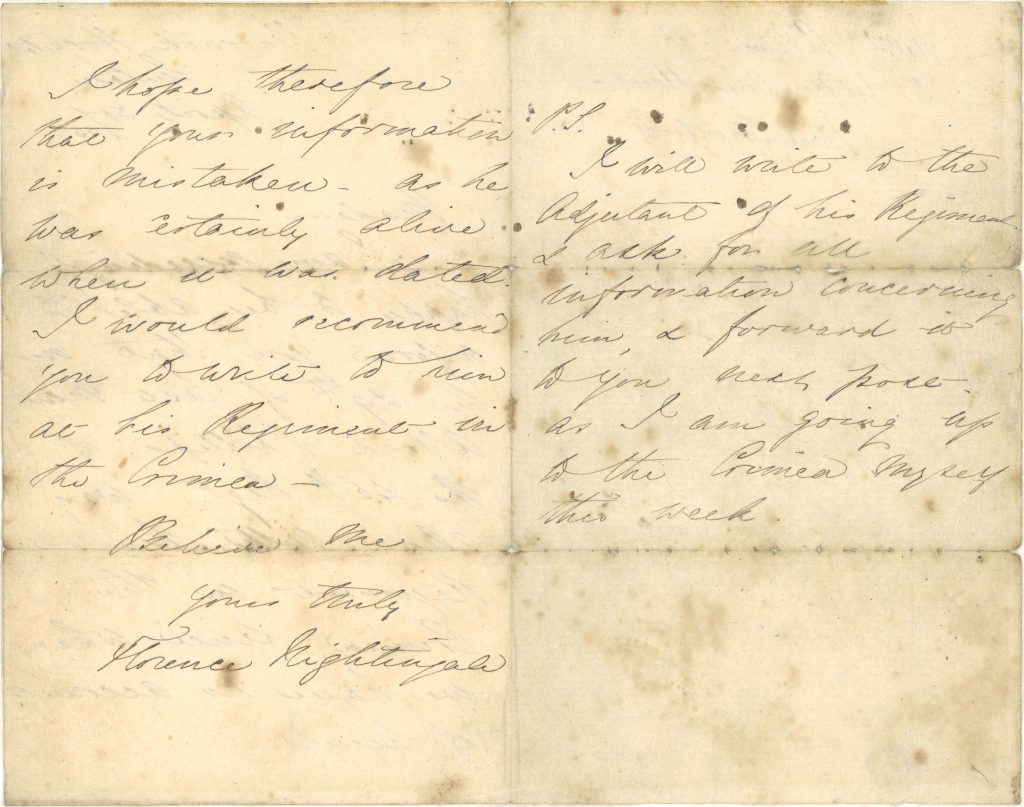

Florence Nightingale cared for men of the 46th Regiment at Scutari hospital. In the letter above she writes:

“Madam

I am exceedingly happy to be able to inform you that on the 29th of last month, Alfred Phillips, of the 46th Regt. was alive with his regiment in the Crimea, since when we have no account of him.

I hope therefore that your information is mistaken – as he was certainly alive when it was dated. I would recommend you to write to him at his Regiment in the Crimea.

Believe me

Yours truly,

Florence Nightingale

PS. I will write to the Adjutant of his Regiment & ask for all information concerning him, & forward it to you next post as I am going up to the Crimea myself this week.”